Beyond beach body social media doom scrolling there are serious global health consequences from obesity. Dr Bharadwaj Chada and Dr Michelle Tempest at Candesic consider the trends in the weight loss sector and why now is the time to problem solve, consolidate and invest

Beyond beach body social media doom scrolling there are serious global health consequences from obesity. Dr Bharadwaj Chada and Dr Michelle Tempest at Candesic consider the trends in the weight loss sector and why now is the time to problem solve, consolidate and invest

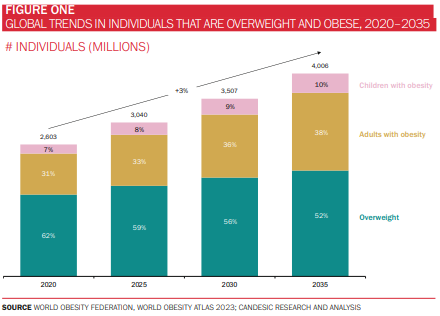

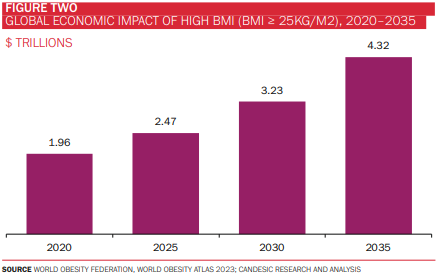

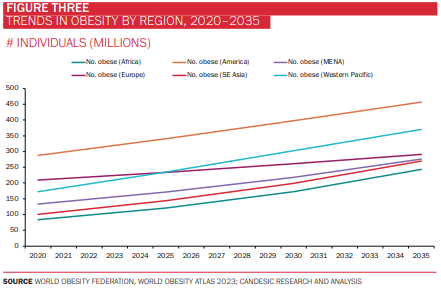

Obesity remains one of the most pressing public health challenges of our time. More than half of the world’s population is projected to be overweight or obese by 2035, with an estimated economic impact of $4.3 trillion (around 3% of global GDP). Notably, the prevalence of obesity is increasing most steeply in South East Asia and Africa (at a CAGR of almost 7% in the case of the latter), although the Americas continue to account for the highest proportion of individuals with obesity (figures 1-3). It is scarcely surprising, then, that efforts to curb this global epidemic have been the mainstay of policymaking and R&D activity for decades.

The obesity drug market

Despite its global burden, the discourse surrounding obesity had, in recent years, succumbed to ennui and background noise, a victim of everchanging priorities (not least because we had a global pandemic to contend with). The approval by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) of Novo Nordisk’s controversial weight loss drug, Wegovy (semaglutide), in April this year has reignited the debate, bringing issues such as health equity, safety and health economics to the fore. With Eli Lily’s Mounjaro (tirzepatide) also on the horizon (NICE’s recent rejection notwithstanding), the treatment paradigm and market opportunity for obesity investors appears to be firmly at an inflection point.

To be clear, Wegovy is not the first weight loss medication approved for use in the NHS (nor is it the first of its kind, a class of drug known as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists). Orlistat, a drug that prevents the absorption of certain dietary fats, has been approved since 2010 for patients with a BMI of 28+ with associated conditions (such as high blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes), or 30+ without associated conditions.

A decade later, Saxenda (liraglutide) was approved. This works by acting on GLP-1 receptors throughout the body to promote satiety, slow gastric emptying, and improve insulin sensitivity. Saxenda is only available following consultation with a specialist weight management service and is currently indicated in adults with a BMI of 35+ (or 32.5+ for at-risk ethnicities), non-diabetic high blood sugar and cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure, and high cholesterol.

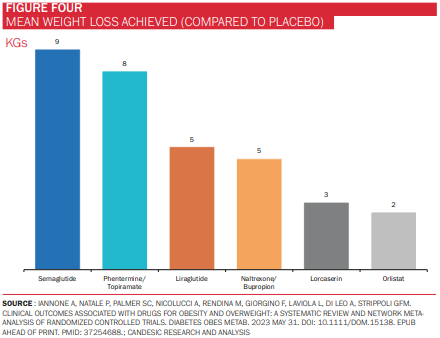

In addition to semaglutide, orlistat and liraglutide, there are three further FDA-approved weight loss medications in the US: buproprion-naltrexone, phentermine-topirimate, and setmelanotide.

The fanfare surrounding semaglutide has not, therefore, been for a want of alternatives, but rather due to its superiority over them. In a 2023 systematic review of the effectiveness of several obesity medications, semaglutide achieved the greatest mean weight loss, a finding that was echoed in a 2022 JAMA paper comparing semaglutide with liraglutide (figure 4).*

There is evidence to suggest that tirzepatide, currently approved for use as a diabetes medication but not yet as a weight loss drug, is superior still to semaglutide. Sold under the brand name Mounjaro by Eli Lily, tirzepatide is a joint GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP-1) agonist, which further promotes the release of insulin and loss of weight.

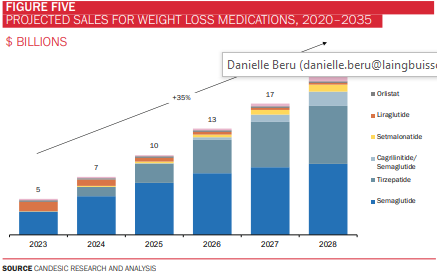

Taken together, GLP-1 agonists have captured the imagination of drug manufacturers, clinicians, patients, and celebrities, such as Elon Musk and Kim Kardashian, alike. Analysis by Komodo analytics revealed that five million prescriptions for semaglutide and tirzepatide were written in 2022 – up 2000% on 2019 – with a significant proportion of these written for off-label use (i.e. in non-diabetic patients). Indeed, sales for weight loss medications are projected to reach $21bn by 2028, almost all of which will be from GLP-1 agonists (figure 5). Another estimate by investment bank Jefferies puts the global GLP-1 agonist market at $150bn by 2031.

Obesity & Health tech

Sitting adjacent to pharmacotherapy, healthtech companies operating in this arena have also enjoyed considerable success in recent years. This has been enabled, thanks in part, to the NHS Digital Weight Management Programme (DWMP), which was launched in July 2021 as part of the NHS Long Term Plan. The DWMP is a free, 12-week programme that delivers diet and exercise advice, as well as behavioural and motivational resources, for individuals with a BMI of 30+ and a diagnosis of diabetes or hypertension. Patients are referred onto the DWMP by their GP and the programme is delivered by organisations such as Liva, Oviva and Xyla Health & Wellbeing.

Digital health technologies may be used throughout the obesity care delivery pathway, from the prevention and screening of at-risk individuals; delivering health coaching and counselling (either through teleconsultations, or automated, AI-powered tools); monitoring progress and response to treatment over time (including using IoT-connected devices); aiding behavioural change through gamification and ‘nudging’; and providing peer support through online social networks. The evidence generally casts a favourable light on these products and services, in some cases

demonstrating superior outcomes compared to face-to-face services. For example, US chronic-disease management company Virta Health demonstrated a statistically significant and comparable reduction in weight in the telemedicine (intervention) arm during the Covid-19 pandemic, compared to an in-person (control) arm from two years prior. Meanwhile, a 2020 observational study of 250,000 overweight individuals in China involving the use of a commercially available digital health application, ‘MetaWell’, a smart weighing scale and a nutrition plan, led to a mean weight loss of 5.4kgs, with 63% of participants losing at least 5% of their body weight. Encouragingly, digital health weight management tools appear to also be well received by children and minority groups, such as individuals in low-income settings and pregnant women, when used both as an adjunct to, as well as replacement for, traditional office-based services.

To prescribe, or not to prescribe?

Many weight management companies now find themselves at a crossroads, as they face the decision of whether to embrace the zeitgeist and enter the GLP-1 bullring. Candesic analysed 40 weight management companies and services, including industry titans such as Weight Watchers and Slimming World, successful startups (Noom, Omada, and Oviva), and up-and-comers (Alfie and BeyondBMI), in order to determine the breadth of their service offerings, as well as their position on drug prescriptions. Of note, this analysis only focussed on weight management platforms and services, and not on companies offering a specific point-solution, such as a diagnostic test or single treatment.

We found that 63% of companies analysed were providing prescription weight loss drugs in addition to offering weight management services, while 37% were offering services alone. Progress tracking (for example of meals, weight, and physical activity) was the most common service, followed by online resources – such as videos, exercises, and activities – and support from a dietician or health coach (either synchronously, or asynchronously). Of the companies that were offering weight loss medications, Saxenda was the most commonly prescribed drug, which is unsurprising given its approval for weight loss in many regions of the world. Wegovy, Ozempic, and Mounjaro were also prescribed frequently; in the case of the latter two, this represents an off-label prescription on the part of these companies. Of the companies studied, 57% were headquartered in the US, although this figure rises to 72% when considering only those companies with prescribing capabilities. This may be attributable to the more established private medication market and higher levels of cost-sharing in the US.

For non-US companies with prescribing capabilities, Swiss firm Oviva and UK startup Numan are the largest, with an employee headcount and fundraising value of 600 and $113m, and 140 and $78m, respectively. Oviva prescribes GLP-1s only in conjunction with a behaviour change programme in reimbursed settings in the UK and Switzerland, whilst Numan offers a range of private-pay GLP-1 agonists.

The shifting sands of obesity healthtech

Most telling in all of this has been the strategic decisions that many of these companies have taken in recent months, perhaps presaging changes in the broader obesity healthtech landscape. It has been revealing to observe which side of the GLP-1 debate companies are currently coming down on, and more instructive still, will be whether these firms dance to a different tune once the size of the prize begins to manifest itself in coming years.

Household name, WeightWatchers (recently rebranded to WW), which posted revenues in excess of $1bn in 2022, has laid bare its intentions to enter the drug market with its $106m acquisition of Sequence early this year. Sequence is a virtual weight management program that offers members a range of GLP-1s and other weight loss medications. Similarly, Noom, with its erstwhile focus on psychology and motivational techniques, launched ‘Noom Med’ in May of this year, granting eligible members access to range of weight loss drugs. And telemedicine giant, Teladoc, has also launched a ‘Provider-Based Care’ weight management service, enabling its providers to prescribe GLP-1 agonists.

In contrast, other companies are yet to board the GLP-1 hype train, though only time will tell how long they remain tethered to the platform. US chronic disease management companies, Lark and Virta, both having raised funds in excess of $200m, are conspicuous in their absence, the latter in particular continuing to emphasise nutrition, lifestyle interventions, and deprescribing. Unicorn Omada Health has also decided to eschew pharmacotherapy, instead launching a GLP-1 specific programme that provides behavioural support and coaching to its members already on the drug.

Implications for the future

In defence of the obesity healthtech companies that have taken to prescribing medications, seldom is drug therapy the only weapon in their arsenal. In keeping with recommendations issued by NICE, the FDA, and various other obesity experts, GLP-1s are often administered in tandem with holistic, multidisciplinary behavioural and lifestyle interventions, such as counselling, progress monitoring, and peer support. For example, Calibrate Health offers members a year-long ‘Intensive Lifestyle Intervention’ (ILI) programme, that combines coaching, online lessons, and tracking of various health behaviours. When used alongside GLP-1 agonists, such as Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro (Calibrate’s doctors prescribe only GLP-1s due to the stronger evidence base for these drugs), a real-world cohort of over 2,500 members achieved an average 15% weight loss, exceeding the use of these drugs alone.

Indeed, it is this synergistic, two-pronged approach combining pharmacotherapy with behaviour change that is likely to achieve more meaningful results than either intervention in silo. Oviva also demonstrated greater weight loss in participants receiving both remote lifestyle coaching and liraglutide (~14kgs), than those receiving only the former (~7kgs). While companies offering this hybrid approach should be cautiously encouraged, perhaps the greater cause for concern is the private pharmacies peddling GLP-1s with little specialist oversight or post-prescription support. Sam Winward, head of commercial at Oviva, further advocates for this combination of behaviour change and pharmacotherapy.

‘Without an accompanying dietary and behavioural change support, patients can experience nutritional deficiencies, a loss of lean muscle mass and will not be equipped to cope after the course of medication ends. To get the most out of treatment, it is critical that patients are not left unsupported, as often happens in the self-pay market,’ says Winward.

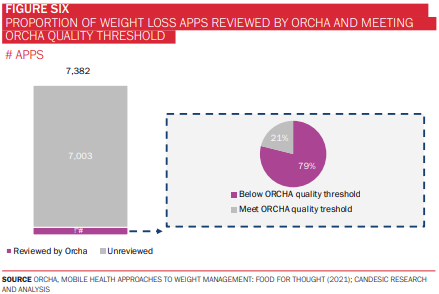

There are also several other fundamental questions that must be addressed if these tools are to be used at scale, particularly in the context of a public health system like the NHS. As of 2021, very few of these technologies had been reviewed and accredited by bodies such as the Organisation for the Review of Care and Health Apps (ORCHA), with fewer still meeting ORCHA’s quality threshold, assessed across a range of domains, including clinical assurance, data privacy, and user experience (figure 6). This has important implications for both developers, in releasing high quality, safe applications, and regulatory bodies, to build capacity and stay atop this burgeoning landscape.

Moreover, there’s the question of access and health (in)equity. There have already been significant supply chain disruptions and delays in Wegovy arriving to UK shores, in spite of the fact that the drug has only been approved for individuals referred to the NHS Specialist Weight Management Service (for adults with a BMI of 40+, or 35+ with co-morbidities). Such is the extent of the shortage, that a recently published National Patient Safety Alert has advised against initiating new patients on GLP-1 agonists, especially for off-label indications, with market demand unlikely to be met until mid-2024.

With the recent announcement of a £40m, two-year pilot enabling GPs to also prescribe Wegovy in the community, these constraints are only likely to be amplified further. Wegovy and its GLP-1 siblings, then, run the risk of being the holy grail that remains just beyond reach. To compound the supply-side challenges, the increasing consumerisation of healthcare has led to a flourishing private market in the UK, and patients’ willingness to pay out-of-pocket for their medications may impose demand shortage too.

Finally, a word on the future of the obesity treatment paradigm. There is some consensus that obesity is a chronic condition that must be managed, and not cured, and thus ‘miracle’ drugs such as Wegovy may be sending the wrong message to individuals struggling with their weight. There is a concern that pharmacotherapy addresses the symptoms rather than the cause of obesity, a plaster over the crack of a broader biopsychosocial complaint. Indeed, studies have reported a ‘rebound’ weight gain upon discontinuation of the drug, in some cases exceeding the patient’s baseline weight, further strengthening the case for the multidisciplinary approach described earlier in this article.

To that end, John Feenie, CEO and Founder of the College of Contemporary Health (CCH), which provides training for obesity practitioners, says: ‘There are a number of different models for the treatment of obesity, but it seems that the most successful, and therefore enduring, ones will use some combination of weight management, medications, personalised behavioural change, and AI technology.’

Regulatory bodies must remain vigilant against ‘get-rich-quick’ pharmaceutical companies heralding GLP-1s as the panacea for all ills.

Conclusion

As ever in healthcare there is no magic bullet, no cure-all pill but instead the solution is teamwork – a network of policy makers, investors, medications, technology, education and behavioural support. Globally, the obesity issue remains chronic with serious economic and social consequences. There is finally a sense of urgency in this sector and with consolidation and partnership opportunities there will also be winners in the return on investment.

*It’s worth noting that semaglutide had already been available on the NHS as an anti-diabetic injection (Ozempic), and pill (Rybelsus), although these preparations contain different amounts of semaglutide compared to Wegovy. Wegovy has been shown to achieve a superior decrease in bodyweight compared to the other formulations.

©2024 All rights reserved LaingBuisson

©2024 All rights reserved LaingBuisson