As widespread community testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies gets underway, will society be divided into the ‘immunes’ and the ‘non-immunes’? Dr Joe Taylor, principal at Candesic, examines the potential of ‘immunity passports a key to the lockdown

‘Immunity passports’ have been touted as a tool to get the world economy back on its feet as fast as possible, but risk driving the emergence of an underclass of immunologically vulnerable people whose liberty continues to be curtailed while their neighbours are free to get their lives back on track.

In early April, Matt Hancock announced that the government was considering an ‘immunity certificate’ to ‘get back as much as possible to normal life’.

The possibility of getting people back to work and relinquishing them from isolation as early as is safe is attractive, although accompanied by political and societal dangers, alongside practical challenges.

What is an Immunity Passport?

The concept of an ‘immunity passport’ rests on three key tenets. Exposure to SARS-CoV-2 generates an immune response that persists beyond the duration of active infection, the persisting immune response is protective against reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and that it is possible to test, through antibody serology, if a person has this active immunity.

There are already private providers of ‘immunity passports’. Florida-based Avers LLC offers a range of certifications enabling people to instantly substantiate an individual’s medical or health status based on verified documents submitted by a medical laboratory or physician, including STI status, drug free confirmation and ImmuniPass. ImmuniPass is being specially marketed to enable people to confirm they have immunity against SARS-CoV-2. With no government or regulatory backing, the ImmuniPass is currently only useful to demonstrate to friends and family that you are safe should you wish to skirt the current lockdown rules, but in future it could provide the basis of a more formal ‘immunity passport’.

Potentially, the government could establish a register of those who are immune and issue ‘immunity passports’ enabling them to circumvent the current lockdown restrictions. While many governments are considering what if any role ‘immunity passports’ would play, there has been no confirmation that the UK government will introduce them. However, this article considers the potential implications should ‘immunity passports’ become part of the exit strategy.

How will the UK move out of lockdown?

The UK government has not detailed its plans for exit from lockdown, although it is likely that there will be a stepwise easing of restrictions, and that identified groups and specific individuals, perhaps those groups least likely to suffer from the severe form of the disease, will be able to return to aspects of pre-Covid-19 life.

However, policing who is and who isn’t permitted to live outside of the restrictions will be challenging without some form of certification.

Does prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2 result in immunity?

The hypothesis that exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and survival of any Covid-19 symptoms will confer immunity to clinically significant reinfection is yet to be proven.

Although the coronavirus that causes the common cold produces a weak immune response lasting only a matter of months, other coronavirus diseases SARS and MERS potentially produce long-lasting immunity. Data is limited because both viruses have infected far fewer people than SARS-CoV-2, but SARS-CoV-1, the virus that causes SARS, has a genome that is 76% similar to that of SARS-CoV-2 and we should therefore expect a similar pattern of post-infection immunity in both instances. A 2007 study reported in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, detailed evidence of high levels of SARS specific antibodies in a group of 176 survivors. This immune protection remained strong for two years, with their immune response starting to wane in the third year.

The assumption that high titrates of specific SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in the plasma protect against infection forms the basis of the ‘immune passport’ thesis. Further widespread antibody testing, and patient follow-up will be required before a definitive answer can be reached.

How would immune status be determined?

Current methods of testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection use PCR to identify the virus in the blood, but this technique is only effective in the detection of active infection and does not indicate the likelihood of post-exposure immunity. Measurement of antibodies against parts of SARS-CoV-2 specific to that viral strain is highly indicative of prior exposure, and potentially of ongoing immunity to reinfection, but the serological testing is challenging. To date, progress to develop a diagnostic measure that effectively identifies those who have been exposed to the specific SARS-CoV strain that is at the heart of the global pandemic has been slow.

Several ambitious programmes to test for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies have now been launched around the globe. The World Health Organisation’s Solidarity II study will pool antibody data from more than half a dozen countries. In the US, a collaborative multi-year project has been established to provide a picture of nationwide antibody prevalence.

Should the titrate and specificity of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in plasma prove to correlate with the extent of immunity to Covid-19, then this would form the basis of tests to determine immunity status and therefore the foundation of ‘immunity passport’ issuance.

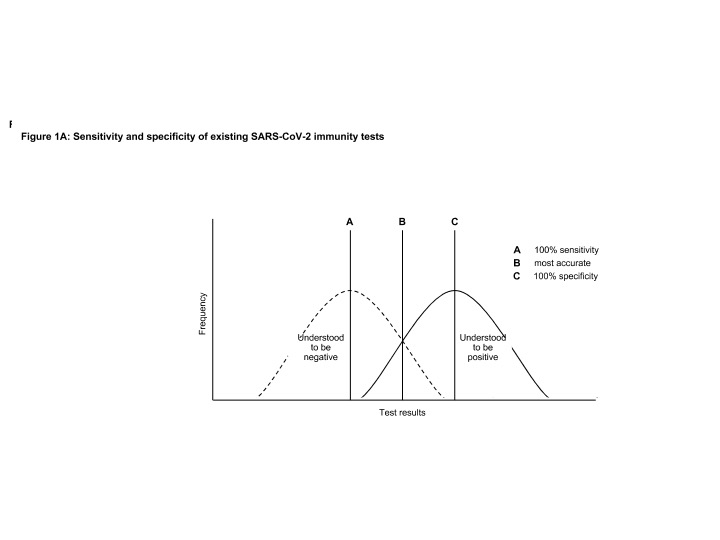

Diagnostic tests are imperfect and can produce both false positives and false negatives (Figure 1A). Cellex, which was the first company to get a rapid SARS-CoV-2 antibody test approved by the FDA, has a sensitivity of 93.8% and a specificity of 95.6%, which is pretty impressive but still means there would be people who are immune excluded from an ‘immunity passport’ and people with false positive results potentially endangering themselves and others.

In general, you can tweak sensitivity and specificity of an existing test to reduce the risk of false positives or false negatives but usually not both. There has to be a decision made as to whether the issuance of ‘immunity passports’ could be on the basis of those with the fewest false positives to minimise viral transmission risk, or a test with the lowest false negative results to guard against the unnecessary curtailment of liberty. Consequently, the test for ‘immunity passport’ status may be different to that required for epidemiological and policy purposes.

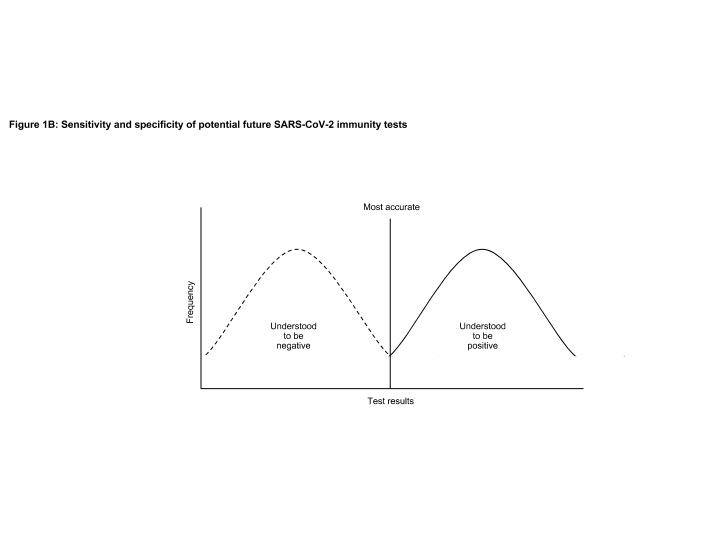

As evidence accumulates regarding the antibody titrate levels and molecular features that confer immunity, alongside other features determining immune status, the true negative and true negative curves can be pulled apart (Figure 1B), reducing the requirement to compromise between sensitivity and specificity.

Even with perfect knowledge of the SARS-CoV-2 immune response, any determination of immunity against Covid-19 would also need to consider additional factors. The presence of antibodies is not the only factor determining a person’s response to viral exposure, we may establish genomic markers for reinfection exposure risk, the impact of co-morbidities and ongoing medications such as immunosuppressants. The more research that is done on the determinants of reinfection risk the greater our ability to pull apart the two curves and move from a probabilistic determination of immunity status to a more binary answer. With this anticipated improvement in immune status, determining the rationale for ‘immunity passports’ will be bolstered.

How would Immunity Passports work in practice?

The issuance of ‘immunity passports’ would, of course, be dependent on having a reliable serology test for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, and for this to be deployed. Given there is likely to be limited capacity for testing there will have to be prioritisation by government of who gets tested and therefore who has the possibility of being granted an ‘immunity passport’.

In the first instance, key workers are likely to be at the front of the queue. In the UK, according to a recent RCP survey, 15% of doctors are currently unable to work because of illness or self-isolation resulting from suspected Covid-19 in a member of their household. Re-mobilising key workers, especially those in high risk health and social care roles, will be essential to avoiding erosion of the system to the point of collapse.

Once ‘immunity passports’ are issued to key workers to support their return to work, a Pandora’s box of possible tiered rights to freedom is opened.

The government will have to consider if those with known or likely immunity should have other liberties restored. For example, could people with positive serology congregate together. Will there be pubs open only to the immune? Immune-only football matches? Immune-only marriages?

How would a person prove their immune status?

Whenever a bureaucratic system is in place to control individuals’ access to significant liberties, there will be people who seek to find its weaknesses. An ‘immunity passport’ system will require an efficient and easy means for an individual to present to policing authorities’ their status, and for their status to be reliably checked against a central register.

There would be a requirement for a national, or perhaps international, database to track immunological status. Although not lauded with acclimation, a number of existing technology companies already operate comparable systems for UK government bodies.

In 2017, Kainos Software was awarded the £3.2bn contract to become the delivery partner of the HM Passport office for online passport applications services. The team was engaged to iteratively design, build and implement digital services for UK passport holders to provide documentary evidence in support of applications.

The digitisation of the UK passport system has not been without its critics. There have been implementation delays and architectural issues common to large public software projects. There has also been criticism of automated healthcare status processing, by which some people have been inappropriately denied passports due to inaccurately processed documentation.

A £91m outsourcing contract with the French company Sopra Steria to bring more visa processing functions online has been beset with difficulties since its launch at the end of last year. The system uses so called ‘black box algorithms’, which have come under fierce criticism for the way racial profiling has been used to identify people at increased risk of bringing infection into the country without actually declaring the parameters they are considering or their validity.

Electronic health records might be the most sensible place to store the immunity status of patients, although the system is a mess with fragmented provision and failures in interoperability. To burden these systems with another function is a risky strategy.

Public trust in government to manage healthcare data is fairly abysmal, and it may fall on a much newer entrant to the market to implement ‘immunity passports’. Bizagi, a UK-based technology, company has released ‘CoronaPass’, an app that will use an encrypted database to store information about users’ immune status, based on antibody test results provided by hospitals or other healthcare providers. The app would present a QR code that a government or company official could scan to certify an individual’s immunity status has been verified, allowing them to return to work, board an airplane, or otherwise relax their social distancing. Bizagi is HIPAA compliant and won’t hold any patient data other than immune status. Data would be kept in an encrypted cloud database accessible only to governments or companies that are able to use the ‘requesting’ side of the app. Patients can delete their profiles any time and the company recommends that photo ID is used alongside the app to prevent fraud.

Irrespective of who holds the central register of immunity status and associated rights to freedom, there remains the practical issue of an individual being able to demonstrate their status and the rights they hold.

Verification of immune status could be done via an RFID chip on a new identity card, or via a mobile app, to gain access to certain areas. For example, cinemas, music venues or even public transport. However, the opportunity for immune status to be forged or shared is a real possibility with these solutions.

Will access to care be dependent on immunity status?

The Equality Act 2010 recognised HIV as a disability from the point of diagnosis, regardless of whether or not the virus had manifested in physical illness. Should SARS-CoV-2 immunity status come under the same regulatory umbrella then there are significant regulatory implications of introducing ‘immunity passports’.

During the lockdown period, many primary healthcare providers have abandoned face-to-face appointments and moved to remote consultation. Disadvantages of telemedicine include the inability to undertake physical examination or collect samples for analysis, a reduced ability to make incidental observations and potential breakdown of the relationships between care providers and patients. Telemedicine undoubtedly will have a far greater role in the provision of diagnoses and treatment following the pandemic, but the ‘laying on of hands’ will remain an important component of good quality medical practice. As face-to-face medical consultations return, will only those with an ‘immunity passport’ have access to them? In such a staged access programme, the care provider could fall foul of the Equalities Act by providing a service of worse quality to the non-immune than they otherwise would.

Residential care providers are likely to face particular challenges in balancing their various and seemingly competitive regulatory requirements. Let us take, as an example, the case of a residential service for vulnerable children registered for two service users. The service has one existing user who has tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, and the Local Authority is seeking to find a placement for a child who both the commissioner and provider believes would be an ideal fit for the service. However, this child is also seronegative. The provider is therefore in a difficult position. Within such services it is almost impossible to enforce social distancing and keeping children whose psychological wellbeing and therapy is dependent on social interaction in isolation is incongruent with good quality care. Here, the preference would be to place a child with immunity into the service to protect the wellbeing of the child already resident, this would meet the duty of care requirements of the provider. However, not placing the child who would benefit most from the service is a breach of the Equality Act in that it compromises the obligation on both commissioners and providers not to provide worse quality care on the basis of a disability.

There seems no easy answer here. Purely from the standpoint of clinical virology, the optimal solution would be to shuffle service users within the system so that ideally all but one service user was seronegative in any service thereby benefiting from herd immunity at a microlevel. However, disrupting stable services by moving children is associated with extremely poor outcomes.

Regular dental check-ups are considered a core element of oral health management, although the evidence is somewhat mixed around the value they bring. Currently in the UK, all routine dental practice has been suspended and only emergency cases addressed either by general dental practitioners or in more specialist settings. Unlike much of medical general practice, dentistry is a discipline that relies more than most on face-to-face examination of the patient and the benefits of telemedicine are limited by the inaccessibility of the oral cavity.

Dentistry is one example, but access to community physiotherapy, psychiatry teams and chiropody, among many other community healthcare services has been curtailed. When these services return then the ‘immunity passport’ is likely to be the ‘golden ticket’ needed to enable community clinical practice to continue in the absence of adequate PPE supplies.

We cannot afford for Covid-19 to be used as an excuse to shirk the responsibility to deliver outstanding care in perpetuity, irrespective of the origins of its need.

And, the path forward?

As we exit the pandemic, we will have to address many challenges of equal gravity to those posed by the infection itself. The inhumanity of isolation can only be borne for so long before the costs must surely outweigh the risks both to health and our way of life.

The tiered freedoms that have characterised the structure of civil liberties during the active pandemic will become more pronounced as lockdown is eased. ‘immunity passports’ are the most likely mechanism by which the government will seek to control the activities of citizens to achieve its objective of continuity of essential services.

Winston Churchill said in 1918 ‘We have won the Great War. Let us win the Great Peace’. We must be as innovative, as steadfast and as resilient in planning for the calm after this storm even while in the eye of it. However, we must also be realistic that the world has changed.

Dr Joe Taylor is Principal at Candesic, a specialist healthcare, life sciences and MedTech consultancy.

©2024 All rights reserved LaingBuisson

©2024 All rights reserved LaingBuisson