Outside of London, NHS PPUs are generally overlooked and underinvested, but as NHS waits continue to rise, they have the potential to generate significant additional income for the NHS. Hugh Risebrow, CEO of Latchmore Healthcare Associates LLP and former commercial director at Guy’s & St Thomas’ looks at the challenges and opportunities PPUs present for the NHS and consultants

Outside of London, NHS PPUs are generally overlooked and underinvested, but as NHS waits continue to rise, they have the potential to generate significant additional income for the NHS. Hugh Risebrow, CEO of Latchmore Healthcare Associates LLP and former commercial director at Guy’s & St Thomas’ looks at the challenges and opportunities PPUs present for the NHS and consultants

The silver lining to post-Covid NHS waiting lists is the growth in private patient activity. Private activity was broadly flat in real terms from 2012 to 2019, and any growth in private hospitals (at least outside London) was driven by treating NHS funded patients. 2022/23 estimates are 25-30% above 2019, with a market now worth c£7bn – c£5bn to hospitals and c£2bn to consultants.

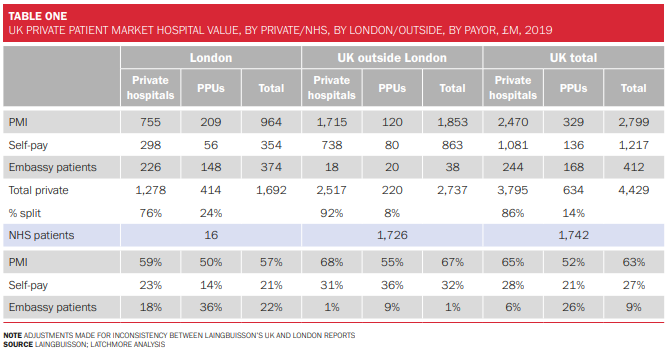

The UK private hospital market is (relative to most international markets) consolidated with five large groups accounting for c75%, and few independents outside London, and these groups (Spire, Circle, HCA, Nuffield and Ramsay) are well known by consultants and patients. NHS private patient units (PPUs) collectively account for around 15% of the market and would be number four in the market if they worked as a single entity.

However, PPUs are all run as individual units by their respective trusts and are heterogenous, and there are major differences between London and outside London. Unsurprisingly. London, with only 15% of the UK population accounts for around a third of private healthcare – affluence and high employer funded PMI mean that there are a range of sophisticated private hospitals, including new entrants such as Cleveland, ASI and Schoen.

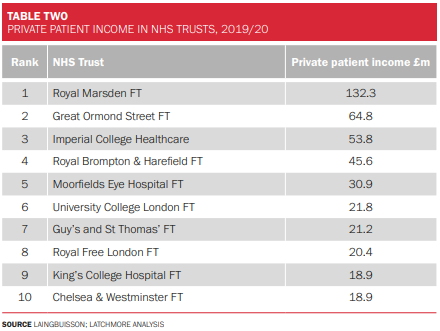

Private patient units in London have a c25% share of this market. The largest ten private patient units are all in London, and in 2019, collectively had over £400m in revenues. The Marsden is by far the largest and thought to be approaching £150m. Some of the larger London PPUs have made substantial investments – Marsden, Brompton (since merged with Guy’s) and Moorfields have collectively invested £15-20m over the past few years in satellite sites in the Harley Street district. This level of investment in PPUs is the exception rather than the rule.

Outside London. PPUs have only 8% of the market. Over 80 NHS organisations have over £1m in private patient revenues, but there is a very long tail of very small PPUs. We would question whether many are profitable, but equally,

“we see most of the potential opportunity for PPUs as outside London.”

The strength of NHS PPUs

With a few exceptions such as Manchester, Leeds, Bristol and Southampton, private hospitals outside London are small with two or three theatres and no or very limited HDU/ CCU facilities. They are geared up to provide a superb service for orthopods performing joint replacements on ASA1-2 patients, as well as a limited range of other high-volume specialties, but in most areas there is insufficient private demand to justify investment in equipment, breadth of staff skills and HDU/ CCU to support low volume, high acuity, or high complexity cases.

By contrast, PPUs should be perfectly placed to meet these needs. Many trusts have invested in specialist equipment for each specialty, such as robots, Linacs and hybrid theatres and have ICU and a range of sub-specialised nurses, therapists, pharmacists and other support staff. Having made the investment in these assets and fixed costs in order to meet their primary objective – treating NHS patients – they should be able to make some capacity available for private patients and make significant financial surpluses which will fund improvements to NHS care.

Latchmore has worked with 16 PPUs and undertaken 1-1 interviews with c300 consultants about their private practice since 2015. Some of our key findings are:

- We estimate that (mainly outside London) c£700m (hospital value) of potentially private practice is treated by the NHS. These are patients who have PMI or are willing to self-pay, but require a treatment which is just not available in private hospitals in their area (they don’t have the facilities or equipment), or in a PPU, and they don’t wish to travel and or have a PMI policy which doesn’t cover London. If these trusts could create a private pathway, they would be getting a cheque for £700m for work which they are doing anyway.

- All things being equal, almost all consultants we have spoken to would prefer to undertake their private practice within their PPU: greater convenience; familiar equipment/ nurses/ IT systems/ governance; superior medical support 24×7 if things go wrong; and, profits support NHS patients. Things rarely are equal, and hence PPUs only have 15% share.

- There is a further £600-800m of activity undertaken in private hospitals where consultants would prefer to do it in a PPU due to the staff and equipment available in the NHS. Add 50% of this to the first bullet and you have the £1bn opportunity.

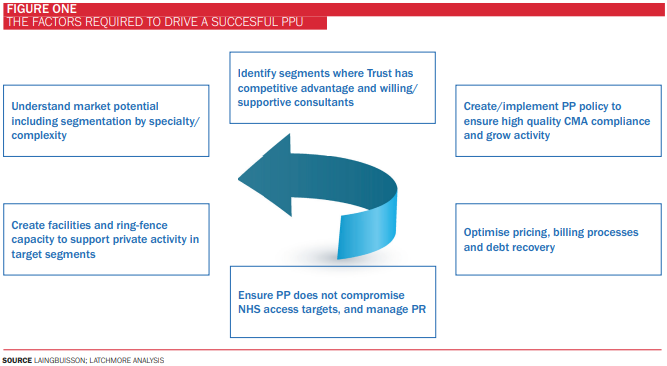

So why don’t PPUs, especially outside London, achieve more? We have developed the schematic below for the factors driving a successful PPU.

In our experience, the following factors mitigate against PPU success (especially outside London):

- Having been an executive director at an NHS Trust, as well as CEO of four private healthcare businesses, I would describe NHS management as a tough gig. Targets and pressure from regional and central offices are relentless, and there is limited bandwidth (outside big London Trusts) to think about private patients.

- Trust execs are keen to avoid adverse publicity. There are plenty of critics (internally and externally) arguing that PPUs are immoral and take capacity from NHS patients. (My view is that clinician time rather than physical capacity is the bottleneck. Once NHS clinicians have performed their allotted time, they are free to work in the local private hospital or do whatever they want, so why not give them the opportunity to work in the PPU?

- PPU management bandwidth. The bigger PPUs have management teams of similar calibre to private hospitals. Smaller PPUs often have highly motivated individuals, but they are expected to combine operational management, with consultant relations, PMI negotiations, billing management, and the work of seven departments in a private hospital group.

- Limited commercial negotiating power and skills. PPUs typically realise prices from PMI 10-20% below private hospital groups. Billing PMI requires specialist skills, and our audits have shown under-billing of 10-20+ %

- Lack of capital. PPUs really only need capital for private day pods/ rooms and consultation rooms, if other facilities are shared with NHS services. Nonetheless, NHS Trusts (except the large London ones described above) inevitably prioritise investment in NHS services.

- NHS access targets. One of the reasons that NHS management is difficult is that ministerial/ political targets to reduce waiting lists, translate through layers of apparatchiks into a brutal performance regime. An element of Trust funding is dependent upon hitting 104% of 2019 activity, whilst many beds are blocked by medically fit patients. Many PPU beds have been handed to NHS patients.

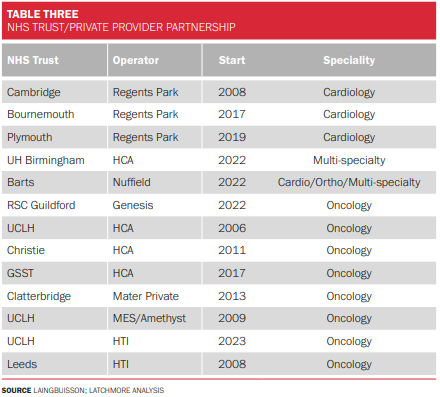

If (and it is a big if) Trusts can overcome these challenges, they could potentially dramatically grow their share of private patient activity. Some Trusts have recognised the benefits of PPUs, but realising that they lack the capital, have created partnerships with private providers. A list of the key partnerships is given below.

Many attempts to create these partnerships have failed (we have a list but I have chosen not to include it) due to internal resistance, management changes and lack of suitable sites within the trust, and private operators are inherently sceptical. Some have done fantastically well. In 2010, The Christie was generating £10m of private patient income with profits unknown. It created a partnership with HCA, which invested all of the capital (c£25m) to create a business which in 2019 made c£13m profit on almost £50m of revenues, with The Christie receiving 49%.

©2024 All rights reserved LaingBuisson

©2024 All rights reserved LaingBuisson